Only a direct exposure of the Church to the peripheries of the world, paired with a critical reflection, can change her perspective on the world and trigger a new imagination of the future of humanity.

On January 20, 1949, US re-elected President Harry S. Truman gave his inaugural speech, known as the ‘Four Points Speech’. He promised “unfaltering support” to the newly born United Nations and to US programmes for world economy recovery. Moreover, Truman pledged to “strengthen freedom-loving nations against the dangers of aggression” and to “embark on a bold new programme for making the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas”.

The speech marked the formal beginning of the race to develop those individuals, people, and nations who, in the eyes of the Western World, were considered “underdeveloped”. From that day, many events happened, primarily the achievement of political independence of the African countries in the decade 1960-1970. Unfortunately, two decades later, almost all African countries had shifted to a one-party political system, crushing the democratic hopes that had been the soul of people’s anticolonial struggle.

However, at the socio-economic level, it was clear that the end of colonialism was, in fact, a necessary passage not to change but to maintain things as they were. Paradoxically, the foreign control of local and national economies increased as the outcome of globalisation, a global process that begun to dominate the world scene from the second half of the 20th Century, under the strict control of the American-European block for its interests.

This ideology did not spare the idea of ‘development’. On the contrary, it was completely emptied of any cultural basis, rendered politically harmless and incapable of any profound social transformation. Instead of uplifting Africa, this approach increased the socio-economic gap between this continent and the rest of the world. Professor Ali A. Mazrui commented: “There is so much of the West in the rest of us that the distinction is hard to make. And that’s precisely the problem”.

Catholic and Protestant Churches also remained trapped in these dynamics. Already considered emissaries of the West during colonialism, they maintained financial and moral supremacy and a ‘salvationist’ and paternalistic approach. All this, in the end, has created more problems than it offered solutions.

In the eyes of a European missionary in Africa today, the failure of both Truman’s plan and a certain social action of the Churches is evident. Christian communities allowed to be tamed in their prophetic imagination of a more egalitarian world, which they should promote. They have increasingly confused the transformation of society towards the highest ideals of a new humanity, a new heaven and new earth, with the simple, mainly material, development of selected areas of the continent and sectors of society.

Building a school or a dispensary may change the life of several people, and the Churches’ immense work witnesses that. Regrettably, it does not touch the systemic level. If the Church never addresses that level, it will appear happy and satisfied with the current order. Logically, who is satisfied never wants to change anything.

Today, speaking of development is highly problematic for at least two reasons. First, the consciousness of development agents of being immersed in such a world system is still insufficient, especially in Church environments. We cannot yet think and do a different development that could lead to an alternative world. We focus on the social analysis of the situation. Still, we lack the prophetic and creative imagination rooted in the biblical and Church traditions.

Second, we do not live any longer in a world divided in a rich, developed North and a poor, underdeveloped South. Today, the division is between the privileged by the world system and its victims at many levels: economic, political, educational, and cultural. Thus, the Church can be a critical voice of the political-economic system and remain entangled in its way of thinking and its strategies for solutions.

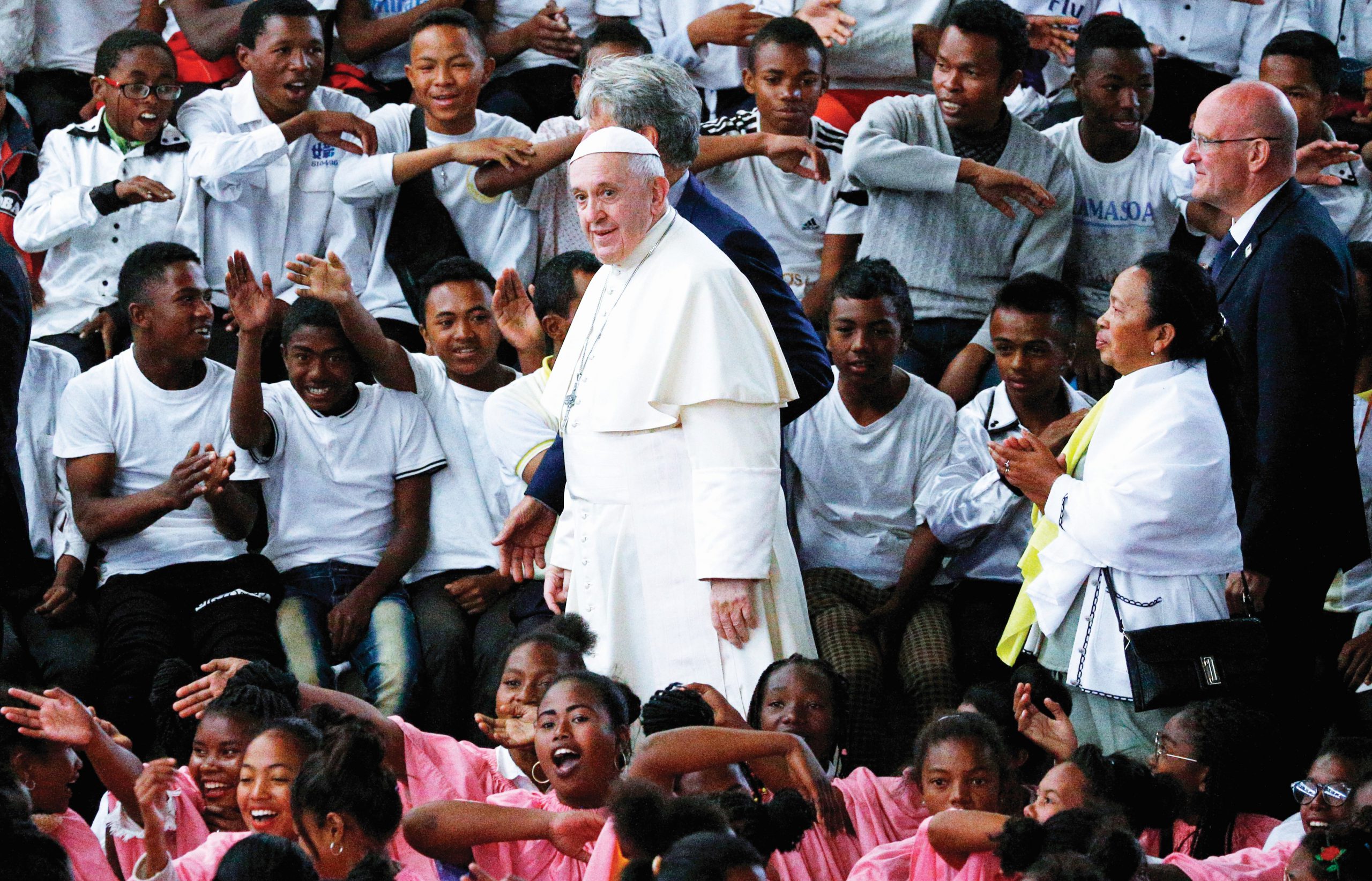

Only a direct exposure to the peripheries of the world, paired with a critical reflection, can change our perspective on the world and trigger a new imagination of the future of humanity. Pope Francis has been repeating this concept like a mantra: “Changing structures without generating new convictions and attitudes will only ensure that those same structures will become, sooner or later, corrupt, oppressive and ineffectual” (The Gospel of Joy, 189). It is challenging but not impossible. The Church must recognise herself as an accomplice of the system. It has to become humble again, before proposing any solution. It has to recognise the poor and allow them to set their priorities.